Are spatial regressions 'significantly biased'?

A raft of recent articles in journals of statistics assert that spatial regression models are ‘biased’. Some are now referring to this supposed bias as ‘spatial confounding’. Red warning flags abound in this literature, and I’ve written elsewhere why I’m personally not convinced by these claims. This post walks through some of the relevant concepts for spatial analysis and examines ‘spatial+’, which is among the more recent proposals for fixing the supposed bias of spatial regression models.

Contents:

- Is ‘spatial confounding’ a problem?

- Looking back at 1993

- Pre-whitening and correlation with spatial data

- Equivalent spatial regression (study 3)

- Is spatial+ biased? (Study 4)

- My conclusion

- R code

- Postscript: Highly-specific prior information

- Bibliography

Is ‘spatial confounding’ a problem?

There is a long history of research on the topic of spatial autocorrelation (SA), including its influence in analyses of covariance and regression. SA refers to map patterns in data values. Any time you can display a variable on a map and find that there is a spatial pattern to the arrangement of values, there’s SA to peak of. SA is ubiquitous in spatial data. It is analogous to serial autocorrelation in time series data.

SA has been a topic of study for more than a century. The work dates back at least to W.S. Gosset and it was even central to his clash with Fisher over experimental designs. Many of the concepts that we work with in spatial analysis today were already present in Gosset’s work. How to make inferences about correlation with spatial data has always been among the core concerns of this work.

As I argue in my article in Geographical Analysis, the newly formed literature on ‘spatial confounding’ is, unfortunately, proceeding as if the literature on SA did not exist. The two bodies of work seek to address some very similar questions but their theoretical frameworks are completely different, as are their bibliographies.

For a sense of what’s going on here, consider the first two sentences of the paper `Spatial+: A novel approach to spatial confounding’ (Dupont et al. 2021) published in Biometrics:

Regression models for spatially referenced data use spatial random effects to account for residual spatial correlation in the response data. As first noted by Clayton et al. (1993), these models can be problematic when estimation of individual covariate effects are of interest.

This is pretty standard stuff for a paper on ‘spatial confounding’ and deserves some comment. The first sentence is mainly pointing out that people use spatial models for spatial data. The second sentence is something I’ve noticed in a number of papers on ‘spatial confounding’. They are attributing their own critique of spatial models to a 1993 paper by David Clayton and others.

I noticed the same assertion found its way into a recent article in Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A (Bobb et al. 2020):

Although spatial modelling is conceptually straightforward, prior statistical literature has shown that it can actually increase bias relative to fitting a non-spatial model, even when there is an important unmeasured spatial confounder (Clayton et al., 1993; Hodges & Reich, 2010; Paciorek, 2010; Page et al., 2017; Schnell and Papadogeorgou 2020). Hodges and Reich (2010) illustrated this potential for increased bias…

In fact, David Clayton and his co-authors argued the opposite of what both Dupont et al. and Bobb et al. are claiming.

Clayton et al. explain why a failure to adjust a regression for SA can easily lead to ‘confounded’ estimates, and they advocate for the use of spatial regression models to fix this. What Bobb et al. and Dupont et al. appear to be missing is that by 1993 there was already an established theoretical framework for understanding SA. The theory has an impressive pedigree (including Gosset, Besag, and many others) and it differs substantively from their own notion of ‘spatial confounding’.

Spatial+ is a method designed to fix a supposed bias in spatial regressions (aka spatial autoregressive models). The spatial+ method is akin to a pre-whitening technique, as I’ll explain below, but with a bit of a wrinkle. Before looking at spatial+ more closely, it will be interesting to look back at 1993, the year of that paper by Clayton et al.

Looking back at 1993

Here is the first sentence of an article by Pierre Dutilleul, published March of 1993 in Biometrics:

Spatial autocorrelation in sample data can alter the conclusions of statistical analyses performed without due allowance for it, because autocorrelation does not provide minimum-variance unbiased linear estimators and produces a bias in the estimation of correlation coefficients and variances. This is well known for the analysis of correlation (in space: see, e.g., Bivand, 1980; Cliff and Ord, 1981, §7.3.1; Richardson and Hémon, 1982; Clifford, Richardson, and Hémon, 1989; Haining, 1990)

In this passage, Dutilleul is expressing the standard view on SA (frequency-theory jargon included): spatial autocorrelation in the data interferes with standard methods and, therefore, spatial analysis techniques are required so that proper adjustments can be made.

Dutilleul goes on to list ‘several solutions’ that were already available for making the appropriate adjustments, including pre-whitening and tend surface analysis. Dutilleul’s paper was a somewhat critical response to Clifford et al.s (1989) article in Biometrics titled ‘Modifying the t Test for Assessing the Correlation Between Two Spatial Processes’. This and other papers by Clifford, Richardson, and Hémon are now standard references in the SA literature (see, e.g., Vallejos et al. 2020).

Looking back, a weakness of the SA literature in that period of time was its unquestioned use of null hypothesis significance testing. However, there was a lot of thorough, very careful work completed. The exchange between Dutilleul and Clifford et al. is exemplary of the care with which the SA literature developed its basic concepts. As a result, the contributions from this period have proven to be of enduring value.

Clayton et al. (1993) were part of this larger literature. Their paper was written mainly for applied researchers in epidemiology. Their comments on confounding and correlation with spatial data would have been perfectly familiar to Gosset, Fisher, Besag, Clifford, Richardson, Dutilleul, and so on.

In the ‘spatial confounding’ literature, the standard papers on SA are rarely referenced. It is almost as if the literature on SA has vanished and we are starting over from scratch.

Pre-whitening and correlation with spatial data

As reported by Dutilleul, among the standard methods to adjust for SA are pre-whitening procedures (see Cliff and Ord 1981; Haining 1991). The term ‘pre-whitening’ is an analogy to white noise: to pre-whiten a variable is to remove any spatial pattern (signal) from the values. You pre-whiten both variables so that you can then apply the old standard statistical techniques to the output of the procedure, like Pearson’s correlation coefficient or OLS regression.

One can use a spatial difference operator to pre-whiten a spatial variable. That is, given some spatially-referenced vector \(x\), you can calculate the average spatially-lagged value of \(x\) using a row-standardized spatial weights matrix \(W\). The weights can be based on binary neighbor criteria or inverse distance. The pre-whitening procedure is then $$\tilde{x}_i = x_i - \rho \cdot \sum_{j=1} w_{[i,j]} \cdot x_j,$$ where \( \rho \) is a spatial dependence parameter that needs to be estimated first. If \(\rho\) were equal to 1, then this simply subtracts the average neighboring value from \( x_i \).

Using matrix notation, the spatial difference operator is $$\tilde{x} = (I - \rho \cdot W) x,$$ where \(\rho\) is the spatial dependence parameter, \(W\) is a row-standardized spatial or network connectivity matrix, and \(I\) is the \(N\)-by-\(N\) identity matrix. This returns the full N-length vector of spatially-lagged values. Or we can say \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} M &= (I - \rho \cdot W) \\ \tilde{x} &= M x. \end{aligned} \end{equation}

It is easy to design a Monte Carlo study to show that pre-whitening two spatial variables can correct for the problems that are caused by SA. After pre-whitening, you can apply a standard correlation coefficient or linear regression to your two variables, \( \tilde{x}_1 \) and \(\tilde{x}_2\). We will walk through each step here, starting with a look at how SA impacts standard statistical results. I'll illustrate with Monte Carlo analysis and then narrate the result using some basic SA theory. After this, we will be better positioned to examine spatial+.

Monte Carlo study 1: SA and OLS regression

We will first write a Monte Carlo program that simply illustrates how SA impacts regression analyses (after, e.g., Bivand 1980). We’ll take the following steps:

- Draw two spatially autocorrelated vectors, \(x\) and \(y\), using a spatial autoregressive model;

- Calculate a regression coefficient and its standard error using OLS;

- Store the estimate and its standard error.

- Repeat many times.

If desired, we can do step 1 in way that adds any non-zero correlation to the two variables.

To complete the first step, we can draw \(n\) values from the standard normal distribution, we will call those \( \epsilon_x \), and then we add SA to them by applying the inverse of the spatial difference operator: \begin{equation} x = M^{-1} \epsilon_x. \end{equation} \( M^{-1} \) is a spatial smoothing matrix. This operation is the same as drawing from the simultaneous spatial autoregressive (SAR) model, which is sometimes called the spatial error model (SEM) when it is specified in this way.

I implement it in R as follows, implicitly referencing the variables to a regular \( 12 \times 12 \) grid (\(N=144\)):

library(geostan)

# N: number of observations (144)

# on a 12-by-12 grid

row = 12

col = 12

N = row * col

# create connectivity matrix (rook adjacency criteria)

W = geostan::prep_sar_data2(row, col)$W

# Spatial dependence parameter

rho = 0.7

# Identity matrix

I = diag(N)

# Spatial difference operator

M_diff = (I - rho * W)

# Invert it to get the spatial smoothing operator

M_smooth = solve(M_diff)Now our variable \( x \) can be produced as follows:

# take N draws from the standard normal distribution

epsilon_x = rnorm(N)

# Add SA to epsilon_x

x = M_smooth %*% epsilon_xI'll create \(y\) from a fresh set of standard normal draws, \( \epsilon_y \), and embed a linear regression relationship with \( x \): $$ y = \beta \cdot x + M^{-1} \epsilon_y. $$

In R:

# regression coefficient

beta = 0.5

# residual scale of y

sigma_y = 0.3

# N independent normal deviates

epsilon_y = rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_y)

# Add correlation with x, and add SA

y = beta * x + M_smooth %*% epsilon_yThis leaves us with two variables, both of which are autocorrelated. Some of the SA embedded in \( y \) is just a product of its connection to \( x \), and some of it is not connected to \( x \). Of the latter portion, some of the patterns will overlap with the spatial patterns in \( x \) by chance and some of them will not. Overall, we have a mash-up of shared and non-shared spatial patterns that need to be sorted out somehow.

At each Monte Carlo iteration, I'll draw these spatially-autocorrelated variables with parameter values of \(\beta = 0.5 \) and \( \rho = 0.7 \) and then fit a linear model by ordinary least squares (OLS). Call this 'Monte Carlo study 1'.

In Study 1, we don't make any corrections for SA when it comes to estimating \(\beta\). We just use OLS and document what happens. The rest of the R code is here (using the variables defined above); complete R code for this post is at the bottom of the page.

## Monte Carlo Study 1

# iterate M times

M = 1e3

# output file

file_1 = "mc_res_1.txt"

set.seed(100)

quietly = sapply(1:M, function(m) {

# draw x from SAR model

x = M_smooth %*% rnorm(n = N)

# draw y from SAR model

y = beta * x + M_smooth %*% rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_y)

# fit regression

fit = lm(y ~ x)

# collect coefficient estimate and its standard error

res = coef(summary( fit ))[ "x" , c("Estimate", "Std. Error") ]

# save results

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

file_1,

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

})

# read results back into R

res = read.table(file_1, col.names = c('est', 'se'))

# Mean estimate

mean(res$est)

# RMSE

err = res$est - beta

sqrt(mean(err^2))

# Calculated standard error

mean(res$se)

quantile(res$se)What we always expect in a study like this one is that the average of the estimate of \( \beta \) is about equal to the value we assigned to it ('unbiased'). And we expect that the calculated standard errors are about equal to the Monte Carlo variability (i.e., the standard deviation of the unbiased estimates). The RMSE in a Monte Carlo study like this ought to be about equal to the analytical standard error.

We see that the average of the estimates of \( \beta \) equals 0.5. This means that OLS is 'unbiased' here. At each iteration, we also collect the standard error of the estimate of \( \beta \); the mean of these standard errors is 0.025. The actual RMSE is 0.038.

So in this case, the estimates are ‘unbiased’ but ‘actual’ RMSE is about 1.5 times the average calculated standard error. This means that the ‘significance tests’ and confidence intervals will be overly confident.

| Mean of M estimates of \(\beta\) | RMSE | Mean of M std. errors |

|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0.038 | 0.025 |

Of course one can change the parameter of the study to yield different quantities and proportions, but adding positive SA to both variables always adds error to OLS estimates. The added error shows up as an increase in RMSE beyond what can be derived from sampling theory with the assumption of independent observations. This illustrates what the geographer Dan Griffith calls the principal property of SA: variance inflation. Here, we see it inflating the sampling variance of a test statistic.

Error and information symmetry

Study 1 shows that SA adds error to the OLS estimates. We need a way of understanding why exactly that error arises. Our equation for creating the data has it that each of our \(N\) observations contains a (fractional) copy of the neighboring observations plus some new information. So each value is a partial duplication of its neighbors. Those partial duplications appear as 'clusters' or map patterns.

With a finite grid space (as it always is), it may be easy for clusters of two variables to overlap one another just by chance. In fact, with high degrees of SA, it becomes difficult to avoid that kind of overlap (or its opposite, a kind of systematic non-overlap). Just try to arrange two variables on a grid in a way that preserves a high degree of positive SA in both variables and near-zero bivariate correlation.1 As SA increases, the number of possible ways to preserve those two properties decreases. When our two variables exhibit positive SA, there are more chances for a big error to occur, and relatively fewer ways that a small error can occur. (The constraints on the organization of the space illustrate how the concept of degrees of freedom has been applied in spatial statistics.)

When two variables share a map pattern, that shared pattern inflates the absolute value of their correlation coefficient. The 'inflation' is illegitimate or deceptive because it arises merely from the duplication of values (as if we had counted the same observation one and a half times). Non-shared map patterns (i.e., autocorrelation patterns that are unique to one of the two variables) deflate the absolute value of their correlation coefficient. Together, these two factors add error to correlation and regression coefficients. That is, they inflate the RMSE of their sampling distributions (Griffith and Paelinck 2011).

Pearson's correlation, like OLS, is 'unbiased' in our first Monte Carlo study because these two kinds of error-inflation factors mutually balanced one another across the \( M = 200 \) iterations. Some iterations have a larger than expected positive error, others have a larger than expected negative error. In some cases, the inflation/deflation factors may effectively cancel out.

From the above description of where these extra errors come from (shared and non-shared map patterns), we find no reason why the added error should be positive rather than negative. This means that our prior state of knowledge is one of information symmetry with respect to the SA-induced error.

The reason studies in spatial statistics tend to be designed like our ‘Study 1’ is that we rarely, if ever, the kind of information that would be required to know or even suspect in advance that an SA-induced error is positive or negative; nor do we have specific information on whether some particular spatial pattern in the data

Our study design here reflects the usual (prior) state of knowledge, which is ignorance with respect to the sign of the SA-induced error. We want our model to identify information in the data, including spatial arrangement, that can guide our inferences with respect to regression relationships and SA (effectively sorting out that mash-up of spatial patterns, cutting out its distortion of covariances).

Monte Carlo study 2: pre-whitening and OLS regression

Pre-whitening simply removes the duplicated information that is latent in the observations. The pre-whitened variates, by definition, cannot have any inflation or deflation factors (at least, they will be reduced to a minimum). Because the source of additional error is no longer present, standard statistical methods should exhibit their usual mathematical properties when they are applied to pre-whitened variables.

Our second Monte Carlo study shows what happens to the OLS estimates when we use pre-whitening. Once again we begin by simulating spatially autocorrelated data, as in $$x = M^{-1} \epsilon_x,$$ and similarly for \(y\). When we proceed to pre-whiten the variables, we are just applying our spatial difference operator, which is the inverse of our spatial smoothing operator: $$\tilde{x} = M x,$$ and similarly for \(y\).

In R code, the pre-whitening procedure could unfold as follows:

# Create correlated, spatially autocorrelated variables

x = M_smooth %*% epsilon_x

y = beta * x + M_smooth %*% epsilon_y

# Pre-whiten them

xtilde = M_diff %*% x

ytilde = M_diff %*% y

# Fit regression

fit = lm(ytilde ~ xtilde)As indicated above, we can implement the pre-whitening stage by applying our spatial difference operator. (Because we know exactly what \(\rho\) is, we don't really have to estimate it.) Alternatively, we can obtain an estimate of \(\rho\) by fitting an intercept-only SAR model to the \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Then the pre-whitened values \(\tilde{x}\) and \(\tilde{y}\) will be the residuals from the intercept-only SAR model.

So our procedure now becomes:

- Draw two spatially autocorrelated vectors, \(x\) and \(y\), using the SAR model;

- Replace \(x\) with \(\tilde{x}\), the residuals from a fitted SAR model;

- Replace \(y\) with \(\tilde{y}\), the residuals from a fitted SAR model;

- Fit an OLS regression to \(\tilde{y}\) and \(\tilde{x}\);

- Store the estimate for \(\beta\) and its standard error.

- Repeat many times.

As expected, the summary of results shows that the mean of the estimates equals 0.50 (it is 'unbiased') and the RMSE of the estimates is almost equal to its theoretical value (where the latter is again represented by the mean of the calculated standard errors). The extra RMSE stems from estimating the spatial dependence parameter; if we skip estimation and just apply the spatial difference operator with \( \rho = 0.7 \), then the RMSE falls to 0.025.

| Mean of M estimates of \(\beta\) | RMSE | Mean of M std. errors |

|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0.027 | 0.025 |

Equivalent spatial regression (study 3)

As mentioned above, pre-whitening is not used very much anymore, at least in spatial statistics. The primary reason is that computational improvements have made spatial regression a trivial thing to apply. The results are nearly the same as pre-whitening for bivariate regression—but of course a spatial regression model is easily extended for multivariate analysis, unlike pre-whitening. Spatial regression models use the information in the data (\(W, x, y \)) to determine whether the SA-induced error is more likely positive or negative. They effectively cut that error out of the estimate (see Donegan 2025 for details).

In our third Monte Carlo study, we follow the same procedure as previously for generating the data, but in the estimation step we use the simultaneous spatial autoregressive (SAR) model: $$y = \alpha + \beta \cdot x + (I - \rho \cdot W)^{-1} \epsilon.$$ The estimates from this model will be tend to be similar, but not identical, to pre-whitening; the two are at least the same in expectation.

The results show that the spatial regression estimate is ‘unbiased’ and it has standard errors that are honest. We are also completely unsurprised that the RMSE for the SAR model is only 65% that of the OLS model. The results are very similar to pre-whitening.2

| Mean of M estimates of \(\beta\) | RMSE | Mean of M std. errors |

|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 0.026 | 0.025 |

Is spatial+ biased? (Study 4)

Dupont et al. present spatial+ as a way to address what they call ‘spatial confounding’. At a glance, what they say is that spatial regressions are biased, and that their method is not biased. If that is true, then spatial+ and SAR (SEM) estimates differ in expectation. This means that if we repeat our Monte Carlo study again but this time use the spatial+ procedure in our estimation step, we ought to expect a definite bias in the spatial+ estimates. The logic is simple: any method that differs in expectation from an unbiased method (e.g., pre-whitening) is necessarily biased.

Spatial+ is a procedure, like pre-whitening, rather than a model. This means we can apply spatial+ using the SAR model. The spatial+ procedure consists of pre-whitening the covariate, \(x\) and then passing it into a spatial regression model. In our case, we will estimate \(\beta\) with the SAR model: $$y = \alpha + \beta \cdot \tilde{x} + (I - \rho \cdot W)^{-1} \epsilon.$$

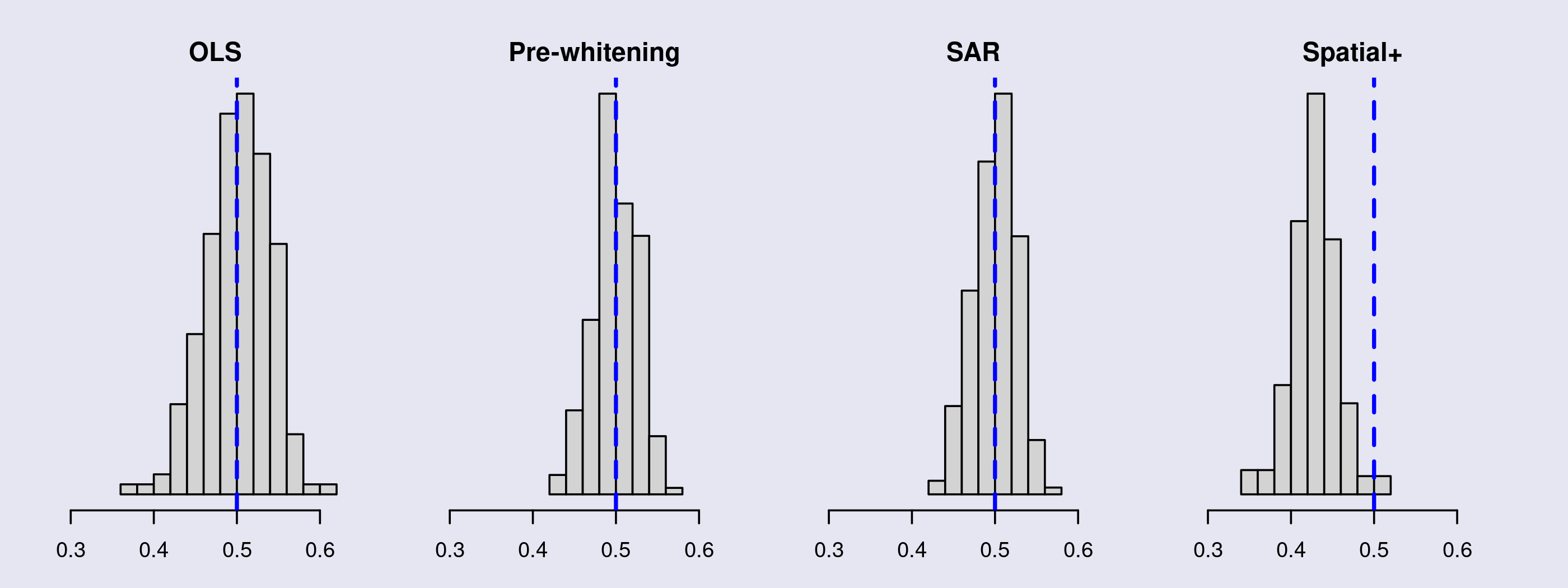

The summary of results shows that the estimates are centered around 0.43, rather than 0.5. Below the table is a histogram of estimates from each of our four models. The blue vertical lines mark out \(\beta = 0.5\). Spatial+ does differ in expectation from OLS, pre-whitening, and proper spatial regression models; therefore, it has a definite bias that is not present in any of the standard methods.

| Mean of M estimates of \(\beta\) | RMSE | Mean of M std. errors |

|---|---|---|

| 0.43 | 0.077 | 0.027 |

I don't have a complete explanation for this result but one possibility comes to mind. Let's say that our two variables \( x \) and \( y \) contain shared and non-shared spatial patterns, as usual. When we pre-whiten \( x \), all of the shared patterns suddenly become non-shared patterns that are unique to \( y \). As we know, non-shared patterns deflate the regression coefficient. Because spatial+ sees all spatial patterns as non-shared patterns (some correctly, others not), it will tend to pull \( \beta \) towards zero.

My conclusion

Unfortunately, it looks like spatial+ is biased in the standard statistical sense of the term. By contrast, spatial regression models have been studied extensively for decades, including in the (spatial) statistics, regional science, quantitative geography, and spatial econometrics literatures. The core concepts that we use for analyses of correlation with spatial data, including experimental treatment effects, date back to Gosset (and certain concepts pre-date Gosset). Here I reproduced the standard Monte Carlo findings that confirm the analytical properties of a standard spatial autoregression. My view is that the problem of ‘spatial confounding’, i.e., a general bias in spatial regression models, does not exist.

R code

R code: Monte Carlo Studies 1—4

# for spatial analysis

library(geostan)

# no. observations

row = 12

col = 12

N = row * col

# create connectivity matrix (rook adjacency criteria)

sar_parts = prep_sar_data2(row, col)

W = sar_parts$W

# level of SA

rho = 0.7

# regresion coefficient

beta = 0.5

# spatial difference operator

m_diff <- (diag(N) - rho * W)

# spatial smoothing operator

m_smooth <- solve(m_diff)

# scale of variation

# controls relative strength of signals

# .3/1 will show biases clearly

sigma_x = 1

sigma_y = 0.3

# MCMC control

iter = 1e3

chains = 1

# store results in these files

f_1 = "mc_res_1.txt"

f_2 = "mc_res_2.txt"

f_3 = "mc_res_3.txt"

f_4 = "mc_res_4.txt"

# iterate M times

M = 200

# Do you want to estimate rho, or use the quick method?

quick = FALSE

# for replication

set.seed(101)

# iterate M times

quietly = sapply(1:M, function(m) {

# Print progress

if (m %% 10 == 0) cat("\n", m)

# draw x from SAR model

x = m_smooth %*% rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_x)

# draw y from SAR model

y = beta * x + m_smooth %*% rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_y)

## Study 1

# fit regression

fit = lm(y ~ x)

# collect coefficient estimate and its standard error

res = coef(summary( fit ))[ "x" , c("Estimate", "Std. Error") ]

# save results

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

f_1,

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 2

rm(fit, res)

if (quick == TRUE) {

# Quick pre-whitening (skip estimation of rho):

xtilde = as.numeric(m_diff %*% x)

ytilde = as.numeric(m_diff %*% y)

} else {

# pre-whiten x

xfit = stan_sar(x ~ 1,

data = data.frame(x = x),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

quiet = TRUE) |>

# we can silence any MCMC warnings about effective sample size:

# the Monte Carlo study itself would reveal any MCMC issues

suppressWarnings()

xtilde <- residuals(xfit)$mean

# pre-whiten y

yfit = stan_sar(y ~ 1,

data = data.frame(y = y),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

quiet = TRUE) |>

suppressWarnings()

ytilde <- residuals(yfit)$mean

}

# regression with pre-whitened variates

fit = lm(ytilde ~ xtilde)

res = coef(summary( fit ))[ "xtilde" , c("Estimate", "Std. Error") ]

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

f_2,

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 3

rm(fit, res)

# spatial regression

fit = stan_sar(y ~ x,

data = data.frame(y = y, x = x),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

slim = TRUE,

quiet = TRUE) |>

suppressWarnings()

res = fit$summary[ "x" , c("mean", "sd") ]

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

f_3,

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 4

rm(fit, res)

# spatial+

fit = stan_sar(y ~ xtilde,

data = data.frame(y = y, xtilde = xtilde),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

slim = TRUE,

quiet = TRUE) |>

suppressWarnings()

res = fit$summary[ "xtilde" , c("mean", "sd") ]

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

f_4,

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

})

# view summary of each 'study'

RMSE <- function(est, b = beta) {

e <- est - b

mse <- mean(e^2)

sqrt(mse)

}

for (f in c(f_1, f_2, f_3, f_4)) {

res = read.table(f, col.names = c('est', 'se'))

summ = cbind(Est = mean(res$est),

RMSE = RMSE(res$est),

SE_mean = mean(res$se) )

print(paste(f, ":"))

print(summ, digits = 3)

}

# plot results

res1 = read.table(f_1, col.names = c('est', 'se'))

res2 = read.table(f_2, col.names = c('est', 'se'))

res3 = read.table(f_3, col.names = c('est', 'se'))

res4 = read.table(f_4, col.names = c('est', 'se'))

png("monte_carlo_comparison.png",

width = 8,

height = 3,

res = 350,

units = 'in')

par(mfrow = c(1, 4),

mar = c(2, 1, 2, 1),

oma = rep(1, 4),

bg = rgb(0.9, 0.9, 0.95, 1)

)

lim <- range(c(res1$est, res2$est, res3$est, res4$est))

lim[1] <- lim[1] - .05

lim[2] <- lim[2] + .05

# ols

hist(res1$est,

main = 'OLS',

xlim = lim,

axes = FALSE

)

axis(1)

abline(v = beta, lty = 2, col = 'blue', lwd = 2)

# pre-whitening

hist(res2$est,

main = 'Pre-whitening',

xlim = lim,

axes = FALSE)

axis(1)

abline(v = beta, lty = 2, col = 'blue', lwd = 2)

# SEM

hist(res3$est,

main = 'SAR',

xlim = lim,

axes = FALSE)

axis(1)

abline(v = beta, lty = 2, col = 'blue', lwd = 2)

# spatial+

hist(res4$est,

main = 'Spatial+',

xlim = lim,

axes = FALSE)

axis(1)

abline(v = beta, lty = 2, col = 'blue', lwd = 2)

dev.off()Postscript: Highly-specific prior information

A premise of our Monte Carlo studies was that our information about SA is symmetric: all of our reasons for expecting the SA-induced error to be positive are balanced by similar reasons that would lead us to expect a negative error. A positive error is no more probable than a negative one. We leave it up to the model (the likelihood) to determine whether the observations point one way or another.

If spatial+ is to be justified, it seems that our prior state of knowledge must differ from the above. The spatial+ procedure, like Thaden and Kneib’s (2018) work, is concerned with making adjustments for a missing, spatially-patterned confounder. This is, obviously, a different question to ask than ‘how should one adjust regression estimates for SA?’

The Monte Carlo studies designed by Dupont et al. and Thaden and Kneib (and others) are designed to see what happens when you ignore a confounding variable which also exhibits SA. They want to show that their own techniques are unbiased when there is a spatially-patterned confounder. Using our own notation and specific techniques, Thaden and Kneib would have us begin our Monte Carlo study by constructing the following variables: $$ c = M^{-1} \epsilon_c$$ $$ x = \gamma \cdot c + \epsilon_x$$ $$ y = \beta \cdot x - c + \epsilon_y.$$ where \(c\) is going to act as a confounder. Dupont et al. add residual SA to \(y\), as in: $$ y = \beta \cdot x - c + M^{-1} \epsilon_y.$$ Now in the estimation stage of our Monte Carlo study, we will pretend that we do not have \(c\). The point of such a study is to say something about how various techniques are affected by the bias that has been induced by this missing confounder.

The required supposition here is that all of the spatial pattern present in \( x \) is the product of a particular, known confounder. (If the supposition is to be supported at all, the confounder must be known.) Compared with our Monte Carlo studies, this represents a far more specific kind of prior information. This is not the usual scenario encountered in spatial analysis, to say the least.

Our last Monte Carlo study repeats all the previous studies, but uses Dupont et al.'s method for generating the data. So we are seeing the impact of a missing confounder, \(c\), on each technique. One can get quite different results depending on the Monte Carlo study parameters; the bias can be positive or negative, large or small, for example. Obviously we want our study design to allow us to identify any bias easily, not to hide it, and I've chosen parameter values with that purpose for all of the Monte Carlo studies.

The results here are not what we should hope for: with a confounder, spatial+ is no less biased than the other methods. In this case it looks about the same as the SAR model. As pointed out by one of Dupont et al.’s discussants in Biometrics, removing part of a confounding (its SA) is not the same as controlling for the confounder.

| Method | Mean of M estimates of \(\beta\) | RMSE | Mean of M std. errors |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.04 |

| Pre-whitening | 0.11 | 0.40 | 0.04 |

| SAR | 0.11 | 0.40 | 0.042 |

| Spatial+ | 0.11 | 0.40 | 0.04 |

R code: Monte Carlo Study 5

##

# Attempt to reproduce Dupont et al.'s way of testing the spatial+ procedure

##

# for spatial analysis

library(geostan)

# no. observations

row = 12

col = 12

N = row * col

# create connectivity matrix (rook adjacency criteria)

sar_parts = prep_sar_data2(row, col)

W = sar_parts$W

# level of SA

rho = 0.7

# regresion coefficient

beta = 0.5

# spatial difference operator

m_diff <- (diag(N) - rho * W)

# spatial smoothing operator

m_smooth <- solve(m_diff)

# smoother for the "spatial confounder"

## (making SA the same as others)

m_smooth_conf <- solve( diag(N) - rho * W )

# as in: y = gamma * confounder + beta * x + e

gamma = 0.5

# scale of variation

sigma_x = 0.2

sigma_y = 0.2

sigma_c = 0.4

# MCMC control

iter = 1e3

chains = 1

# store results in these files

files = list(full_ols = "mc_res_b0.txt",

ols = "mc_res_b1.txt",

pre_whiten = "mc_res_b2.txt",

sar = "mc_res_b3.txt",

sp_plus = "mc_res_b4.txt"

)

# iterate M times

M = 200

# for replication

set.seed(101)

# iterate M times

quietly = sapply(1:M, function(m) {

if (m %% 10 == 0) cat("\n", m)

# draw the 'spatial confounder'

c = as.numeric(m_smooth_conf %*% rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_c))

# draw x: with no SA besides the confounder

x = c + rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_x)

# draw y: contains c twice ('confounder') plus more SA which may or may not shared patterns with c

y = beta * x - gamma * c + as.numeric(m_smooth %*% rnorm(n = N, sd = sigma_y))

## Study 0

# fit the correct regression

fit = lm(y ~ c + x)

# collect coefficient estimate and its standard error

res = coef(summary( fit ))[ "x" , c("Estimate", "Std. Error") ]

# save results

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

files[["full_ols"]],

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 1

# fit regression

fit = lm(y ~ x)

# collect coefficient estimate and its standard error

res = coef(summary( fit ))[ "x" , c("Estimate", "Std. Error") ]

# save results

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

files[["ols"]],

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 2

rm(fit, res)

# pre-whitening:

# pre-whiten x

xfit = stan_sar(x ~ 1,

data = data.frame(x = x),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

quiet = TRUE) |>

# we can silence any MCMC warnings about effective sample size:

# the Monte Carlo study itself would reveal any MCMC issues

suppressWarnings()

xtilde <- residuals(xfit)$mean

# pre-whiten y

yfit = stan_sar(y ~ 1,

data = data.frame(y = y),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

quiet = TRUE) |>

suppressWarnings()

ytilde <- residuals(yfit)$mean

# OLS with pre-whitening

fit = lm(ytilde ~ xtilde)

res = coef(summary( fit ))[ "xtilde" , c("Estimate", "Std. Error") ]

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

files[["pre_whiten"]],

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 3

rm(fit, res)

# spatial regression

fit = stan_sar(y ~ x,

data = data.frame(y = y, x = x),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

quiet = TRUE) |>

suppressWarnings()

res = fit$summary[ "x" , c("mean", "sd") ]

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

files[["sar"]],

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

## Study 4

rm(fit, res)

# spatial+

fit = stan_sar(y ~ xtilde,

data = data.frame(y = y, xtilde = xtilde),

sar = sar_parts,

iter = iter,

chains = chains,

quiet = TRUE) |>

suppressWarnings()

res = fit$summary[ "xtilde" , c("mean", "sd") ]

write.table(matrix(res, nrow = 1),

files[["sp_plus"]],

append = (m > 1),

row.names = FALSE,

col.names = FALSE)

})

# view summary of each 'study'

RMSE <- function(est, b = beta) {

e <- est - b

mse <- mean(e^2)

sqrt(mse)

}

for (f in seq_along(files)) {

res = read.table(files[[f]], col.names = c('est', 'se'))

summ = cbind(Est = mean(res$est),

RMSE = RMSE(res$est),

SE_mean = mean(res$se) )

print(paste(names(files[f]), ":"))

print(summ, digits = 3)

}Bibliography

Probability theory

The above references to ‘information symmetry’ stem from the probability as logic tradition. Clayton provides a great introduction to it. Jaynes is the standard-bearer.

Clayton, A. (2021). Bernoulli’s Fallacy: Statistical Illogic and the Crisis of Modern Science. New York: Columbia University Press.

Jaynes, E.T. (2003). Probability Theory: The Logic of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spatial autocorrelation

Bennett, R.J. and Haining, R. (1985) Spatial structure and spatial interaction: Modelling approaches to the statistical analysis of geographical data (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General). 148 (1): 1—36. https://doi.org/10.2307/2981508

Bivand, R. (1980). A Monte Carlo study of correlation coefficient estimation with spatially autocorrelated observations. Quaestiones Geographicae 6: 5—10. https://ia904602.us.archive.org/3/items/bivand-1980/Bivand%201980.pdf

Chun, Y. & Griffith, D.A. (2013) Spatial Statistics and Geostatistics: Theory and Applications for Geographic Information Science and Technology. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Clayton, D.G., Bernardinelli, L. & Montomoli, C. (1993). Spatial Correlation in Ecological Analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 22(6), 1193–1202.

Cliff, A.D. & Ord, J.K. (1981). Spatial Processes: Models and Applications. London, Pion Press.

Clifford, Peter, Sylvia Richardson, and Denis Hemon (1989). “Assessing the significance of the correlation between two spatial processes.” Biometrics, 45(1): 123-134. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532039

Donegan, C. (2025). Plausible Reasoning and Spatial‐Statistical Theory: A Critique of Recent Writings on ‘Spatial Confounding’. Geographical Analysis, 57(1): 152–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/gean.12408

Dutilleul, P. (1993) Modifying the t Test for Assessing the Correlation between Two Spatial Processes. Biometrics, 49(1), 305–314. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2532625

Getis, A., & Griffith, D. A. (2002). Comparative spatial filtering in regression analysis. Geographical Analysis, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4632.2002.tb01080.x

Griffith, D.A. & Paelinck, J.H.P. (2011) Non-standard Spatial Statistics and Spatial Econometrics. Heidelberg: Springer

Haining, R. (1991). Bivariate correlation with spatial data. Geographical Analysis, 23(3), 210—227.

Legendre, P., Oden, N. L., Sokal, R. R., Vaudor, A., and Kim, J. (1990). Approximate analysis of variance of spatially autocorrelated regional data. Journal of Classification 7: 53—75. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01889703

Richardson, Sylvia, and Peter Clifford (1991). “Testing association between spatial processes.” Lecture Notes-Monograph Series (1991): 295-308.

Rudy Arthur, A General Method for Resampling Autocorrelated Spatial Data, Geographical Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1111/gean.12417

Student [W.S. Gosset] (1914). The Elimination of Spurious Correlation Due to Position in Time and Space. Biometrika, 10, 179–180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2331746

Vallejos, R., Osorio, F. & Bevilacqua, M. (2020) Spatial Relationships between Two Georeferenced Variables. Cham: Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56681-4

Spatial confounding

Bobb, J.F., Cruz M.F., Mooney, S.J., Drewnowski, A., Arterburn, D., & Cook, A.J. (2020) Accounting for spatial confounding in epidemiological studies with individual-level exposures: An exposure-penalized spline approach. Journal of the Royal Satistical Society Series A. 185:1271–1293. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12831

Dupont, E., Wood, S. N., & Augustin, N. H. (2022). Spatial+: a novel approach to spatial confounding. Biometrics, 78(4), 1279-1290. https://doi.org/10.1111/biom.13656

Gilbert, B., Ogburn, E. L., & Datta, A. (2024). Consistency of common spatial estimators under spatial confounding. Biometrika, asae070. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.12181

Hodges, J.S. & Reich, B.J. (2010) Adding Spatially-Correlated Errors Can Mess up the Fixed Effect you Love. The American Statistician, 64(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1198/tast.2010.10052.

Khan, K., & Berrett, C. (2023). Re-thinking spatial confounding in spatial linear mixed models. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.05743

Paciorek, C.J. (2010). The importance of scale for spatial-confounding bias and precision of spatial regression estimators. Statistical Science 25(1): 107—125. https://doi.org/10.1214/10-STS326

Reich, B.J., Hodges, J.S. & Zadnik, V. (2006) Effects of Residual Smoothing on the Posterior of the Fixed Effects in Disease-Mapping Models. Biometrics, 62(4), 1197–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00617.x

Thaden, H., & Kneib, T. (2018). Structural equation models for dealing with spatial confounding. The American Statistician, 72(3), 239–252.

Zimmerman, D.L. & Ver Hoef, J.M. (2021) On Deconfounding Spatial Confounding in Linear Models. The American Statistician, 76(2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2021.1946149

-

This challenge is similar to a classroom lesson that Daniel Griffith liked to use in his spatial statistics course. Also see the papers on correlation with spatial data by Clifford, Richardson, and Hemon (1989) and Richardson and Clifford (1991). Rudy (2011) makes good use of these ideas. ↩

-

I used a Bayesian model to estimate the spatial regression. In place of the standard error what I reported is the standard deviation of the posterior distribution of beta. Since there’s no important prior information here, the posterior distribution resembles the likelihood or sampling distribution. Hence, in the table I still label this as the ‘standard error’. ↩