Are all models wrong? Some mathematical lessons on scientific realism

For some, it seems to be common sense that ‘all models are wrong’. The phrase ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’ is attributed to George Box in reference to statistical modeling (where the phrase is arguably more innocuous), though the underlying attitude is prevalent in many fields. Humility is a virtue, but the statement that all scientific models—i.e., its theories and claims about the structure of our reality—are wrong amounts to something else entirely.

Skeptical views of science can be found in many quarters. Karl Popper popularized the skeptic’s view that all scientific theories are falsehoods waiting to be falsified. The view that scientific models may be gross simplifications, and can rest on falsehoods, remains the dominant outlook in orthodox economics (though it is increasingly besieged). Attacks on the concept of truth itself became common in postmodern theory, followed by some backtracking once the far right clarified the political consequences (oops, too late).

James Franklin’s An Aristotelian realist philosophy of mathematics (Palgrave Macmillon, 2014) is, as the title suggests, a defense of scientific realism for the field of mathematics. He advances the view that mathematics can establish truths about our reality. To do this, he provides a systematic response to the view that mathematics deals only in Platonic ideal-types. Because mathematics may be the most improbable bastion for realism, his argument is all the more provocative.

I find Franklin’s presentation of the realist viewpoint on science to be interesting and largely compelling not despite his focus on pure mathematics (where causality and ethics are more distant concerns) but rather because his focus on mathematics allows him to isolate some essential aspects of realist philosophy.1 He’s a great communicator. In this post I want to discuss one passage from Franklin’s book, where he challenges Einstein’s claim that mathematics is either ‘not about reality’ or else ‘not certain’. To the contrary, Franklin argues that mathematics provides ‘necessary truths about reality’.

Isn’t it obvious?

One reason the phrase ‘all models are wrong’ may appeal to many of us, if I can take a guess, is an unstated premise that a ‘true’ claim is one that perfectly describes empirical things or events. The truth is made up of ‘the facts of the case’. Because theory is by definition an abstraction (from events, things, etc.), any theoretical model must be ‘wrong’ or ‘untrue’ even if it is ‘useful’. If theory is at variance with our complicated empirical reality, what kind of naif would believe that a model could be ‘true’?2

This is perhaps why geographers enjoy reminding us that ‘the map is not the territory’, and chuckle at the king who asked for an accurate map (the map would have to be exactly the size of his kingdom).

The notion that the best theories are gross simplifications, and that it is legitimate for their premises to be known falsehoods, is standard in orthodox economics (the neoclassical theory). One lineage of this is Milton Friedman’s vision for ‘positive economics’ which contends that economic theory need not be about reality, even plausibly so, it just needs to be able to predict human behavior sufficiently well as to offer guidance in practice. Friedman famously states,

Truly important and significant hypotheses will be found to have ‘assumptions’ that are wildly inaccurate descriptive representations of reality, and in general, the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions (in this sense). (16)

The concepts of perfect competition and general equilibrium are examples of such unreal theories. (As James Galbraith and Jing Chen argue, general equilibrium in economic theory is contrary to the laws of thermodynamics, among other things.) The failure of neoclassical economics as a guide to policy was on full display in the 2008 financial crisis.

Among the meanings of the word ‘model’ given by the Cambridge online dictionary is

a simple representation of a system or process, especially one that can be used in calculations or predictions of what might happen.

This provides a good summary of how positivist (anti-realist) philosophy understands models. This definition hinges on the combination of two distinct ideas: the first is ‘simplification’ and the second is ‘prediction’. On this view, a scientist simplifies in order to predict. From this premise, a more ‘realistic’ or less simple model might be taken to be one that incorporates more facts and more complicating factors. That might help to make more accurate predictions. Insofar as theory is just another word for a model, scientific theories must all be simplifications of what is. If this is right, we should all have the humility to admit that all models are idealizations that depart from reality, but they can at least be ‘useful’ for the sake of prediction.

Truth in scientific realism

Scientific realism holds a different understandings of what theory and truth are. I will try to sketch this out before presenting some of Franklin’s ideas. Although some of the contention on this issue stems from different understandings of what scientists actually do and have done historically, the difference of viewpoint may also be described as follows.3

For the realist, abstracting from empirical details does not necessarily take one further away from reality or from the truth. Rather, we use our power of abstraction to identify something specific about our reality - to identify some particular kind of thing. Steel is a particular kind of thing, as are atoms and organisms. The purpose of theory is to understand something about the nature of particular things, often to understand why things have certain properties and not others. A political economist wants to know why a functioning capitalist economy will exhibit a recurring pattern of a wave of growth followed by recession and recovery; a biomedical scientist wants to know why a given chemical has the power to cause cancer. Knowledge of the structure of a thing enables us to understand its causal properties and, if we wish, to make use of them.

By structure, we mean how the parts of this thing are arranged in relation to one another and also what substance each part is made of. This kind of knowledge may or may not enable accurate predictions to be made; predictions are secondary (particularly so outside of a laboratory). And, to clarify this distinction between the realist and positivist outlooks, the realist will say that structures are not necessarily simplifications, they are exactly what lends a thing its causal powers and liabilities. Glass is liable to shatter precisely because of its particular chemical structure.

A realist reply to the pragmatist’s dictum about some theories being ‘useful’ is to ask why scientific theory could possibly be so useful, such a powerful guide to action as to enable the successful development of nuclear power, skyscrapers, vaccines, and so much more. As Andrew Sayer argues, the explanation is that our reality imposes constraints on what kind of ideas can possibly be useful for any particular task. Those constraints enable us to learn some things about our reality.

Genetics proposes, for example, that the double helix structure is remarkably ‘useful’ as a theory because what it posits about genes is true.

But this does not imply that the realist viewpoint is incapable of showing humility. As Harold Jeffreys said of his own ‘critical realist’ philosophy (which is a minor theme of his Theory of Probability),

it is perfectly possible to believe that we are finding out properties of the world without believing that anything we say is necessarily the last word on the matter. (56)

The basic argument of realism, at a minimum, asserts the normative value of holding one’s self to a standard of work for which establishing and testing the plausibility or realism of one’s assumptions and claims is an indispensable component of good theory and good research. It is integral to scientific methodology and, perhaps more to the point, it is germane to the goals of science.

Turning again to economic theory, an alternative to the methodology of neoclassical economics can be found in Anwar Shaikh’s theory of real competition. It is interesting to see how Shaikh describes his work. As he puts it, orthodox or neoclassical economics ‘investigates the workings of a deliberately idealized version of capitalism, from whose vantage point it seeks to characterize the world’ (4). Many heterodox (neo-Keynesian) critics of the orthodox theory also start with a theory of perfect competition but hold that our reality is one of many ‘imperfections’ which are just deviations from the basic theory. His framework differs from both of those:

The goal of this book is to develop a theoretical structure that is appropriate from the very start to the actual operation of existing developed capitalist countries. Its object of investigation is neither the perfect nor the imperfect but rather the real. (5)

This sounds great, but it is not obvious how one is to go about developing theory in that way. How does one devise an abstract theory without venturing into a netherworld of ideal-types?

This is one area where I find Franklin’s book to be relevant to non-mathematicians. Mathematics is quite different from the study of society, and I do not intend to suggest otherwise. So it is all the more interesting that arguments about realism in mathematics should have any important parallels with realist theory in the social sciences. In both mathematics and social science, a key part of the realist argument concerns the question of ‘abstraction’ or ‘theory building’ and how to do it well. In part, this is also a question of perspective, of how we are ‘looking at’ and understanding our own theories.

I am no mathematician, but I will do my best to present a passage of Franklin’s book that speaks to the question of abstraction or ‘theorization’ and its relationship to truth and realism. I’ll come back to economic theory in the end.

A real, universal truth

This brings us to Franklin’s argument that mathematics can obtain ‘necessary truths about reality’. By ‘necessary’ he means that the claims made by certain mathematical proofs are inescapable. By ‘about reality’ he means that the truth pertains to our actual reality, not to an imaginary world or to a Platonic world where mathematical ideal-types are to be found (or, actually, where they are never to be found).

Franklin is taking on Einstein’s claim to the contrary:

As far as the propositions of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality. (cited by Franklin, p. 67)

Franklin responds unequivocally:

Mathematics provides, however, many prima facie cases of necessities that are directly about reality.

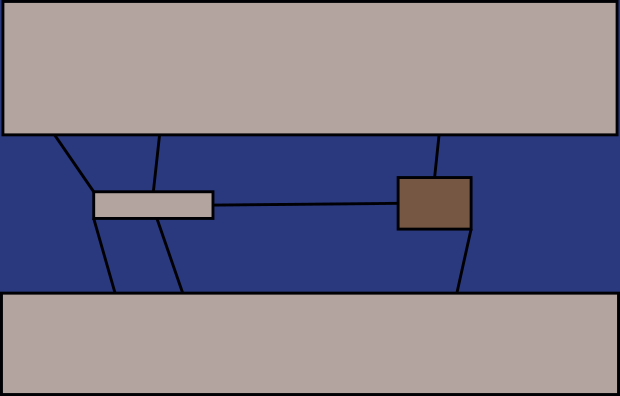

His first example is Euler’s mathematical study of the bridges of Königsberg. The locals believed that one could not possibly traverse all seven of the town’s bridges without crossing at least one of them twice. As in this diagram (or model), there were two islands and seven bridges connecting two riverbanks:

Euler’s work on this problem is now a classic in operations research and network analysis (it was briefly introduced to me once in a quantitative geography course, which remains the extent of knowledge of it). Franklin describes it this way:

Euler proved that it was impossible for the citizens of Königsberg to walk exactly once over (not an abstract model of the bridges but) the actual bridges of the city. (67)

Franklin’s point is that Euler’s mathematical proof applies to anything that shares the abstract structure of the city’s bridges and banks, which can be reduced to nodes in a network. Any truths that necessarily pertain to that structure pertain equally to any and all things that share that structure (it applies to all of its instantiations). It applies to my diagram, for example, if you wish to traverse the lines with a pen.

It is a contingency (not necessary, not guaranteed) that anything should ever have that very structure. Also, it is completely contingent that any thing that does have this structure should not quickly come to have a different structure. But it so happens that the bridges of Königsberg did have that structure, so Euler’s proof applies to them.

A necessary truth, about your bathroom floor

Franklin’s second example is his bathroom floor (and, presumably, your bathroom floor too). As he tells us,

It is a provable proposition of geometry that it is impossible to tile the Euclidean plane with regular pentagons. (67)

If you try, you always find gaps between the tiles. But what do Euclidean planes have to do with reality? A Euclidean plane is an idealization that is presumably not instantiated in any physical object. `If the ‘Euclidean plane’ is something that could have real instances’, he continues, ‘my bathroom floor is not one of them’ (69).

But without embarrassment, Franklin states,

It is impossible to tile my bathroom floor with (equally sized) regular pentagonal lines. (67)

If you purchase square tiles, or hexagonal tiles, you can place them on a flat surface so that they align without gaps between them, covering the entire surface. If there are gaps, they can be always be made smaller by using tiles that are more straight in their edges and right in their angles. By contrast, the gaps between pentagonal tiles can never be closed except by making the tiles something besides pentagons.

So how does he transfer the necessary truth about Euclidean planes to his non-Euclidean bathroom floor? Some academics may be inclined towards skepticism of the argument so far, though a mason, I suspect, would not. But the way Franklin answers this question is valuable regardless of whether you entirely accept the bathroom floor example.

He notes that the mathematical proof has stability:

It is a further fact of mathematics, however, that the proposition of about the Euclidean plane has ‘stability’, in the sense that it remains true of the terms in it are varied slightly. That is, it is impossible to tile…an almost Euclidean-plane with shapes that are nearly regular pentagons. (69)

To finish the argument, he has to address an assumption that many seem to have about shapes. For some reason, squares and triangles are considered more mathematical than the shape of his bathroom floor, even though it, too has an exact shape. You might say that it is a perfect realization of its own, abstract shape.

Franklin says it this way, comparing the original geometric proof to the statement about his bathroom floor:

This [latter] proposition has the same status, as far as reality goes, as the original one, since ‘being an almost Euclidean-plane’ and ‘being a nearly regular pentagon’ are as purely abstract or mathematical as ‘being an exact Euclidean plane’ and ‘being an exactly regular pentagon’. (69)

So if his bathroom has a shape that can be studied by mathematics, which it does, then a mathematical proof about that shape is a proof about his bathroom floor:

The proposition has the consequence that if anything, real or abstract, does have the shape of a nearly Euclidean-plane, then it cannot be tiled with nearly regular pentagons. But my bathroom floor does have, exactly, the shape of a nearly Euclidean-plane. (69)

To return this to the discussion of models, he goes on,

Or put another way, being a nearly Euclidean plane is not an abstract model of my bathroom floor, it is its literal shape. Therefore, it cannot be tiled with tiles which are, nearly or exactly, regular pentagons. (69)

And to add emphasis:

The ‘cannot’ in the last sentence is a necessity at once mathematical and about reality.

In this case, he uses the word model in one of the usual, colloquial ways, which is to signal difference between one’s abstraction and reality; his point, though, is that this case of mathematical reasoning about abstractions (shapes) has real, necessary consequences, or ‘necessary truths about reality’.

Social theory, too?

At this point Franklin is pointing out that mathematics has a way of dealing with abstractions so that they can encompass a range of possible objects, including real things. Then, proofs about the abstractions apply to those real things.

What I take from the above passages is that one should try to specify one’s theory in a way that can encompass real things. Then one can reason, not about a flimsy ideal-type or arbitrarily specified model, but about that more robust (and possibly realized) conceptual system.

Can these ideas be applied to social science? As I was reading Franklin’s book my thoughts often returned to a specific theory, namely Shaikh’s ‘real competition’. His theory is a good example to consider here because everyone is familiar with markets, so the basic concepts can be grasped even if the details and implications are more obscure.4. It is also a highly ambitious theory that has as its object of study a geographically and historically massive, social-physical system, capitalism.

Turbulent arbitrage

The theory of real competition elaborates on the classical theory, as developed especially by Adam Smith and Karl Marx. The theory has been circulating and developing (and splintering) ever since. Key to real competition is the concept of turbulent arbitrage—this refers to the way capital moves from worse to better investment opportunities, where better and worse are defined by the expected rate of profit on new investment. With profitability as its guiding light, capital will flow into sectors where (expected) profit rates on new investment are above average, and out of areas that exhibit below average returns on new investment. Instead of general equilibrium, this theory posits that disequilibrium is giving rise to constant fluctuations.

Fresh investments in productive capacity increase supply and sharpen competition, which will tend to drive those attractive profit rates back down towards the average—and eventually below the average. The system moves from disequilibrium to disequilibrium and these movements are what gives rise to the familiar patterns of aggregate outcomes. The system is chaotic when examined closely but ordered when viewed from afar.5

For a system of turbulent arbitrage to be realized, there are certain material requirements. Private ownership of the means of production would seem to be one of them, the ability to move capital around is another. However, we do not need to assume anything that is highly unusual, false, or impossible—for the theory to apply, we do not need to assume that markets are perfectly liquid, that all production is for profit, that firms are maximizing profits at every moment, that everyone is either a capitalist or a proletarian, or whatever. So far as I can tell, turbulent arbitrage is actually happening, so a natural way to come up with a list of material suppositions would be to examine the actual history of capitalism (which is something Adam Smith and Karl Marx did.)

Concluding thoughts

So far as I can tell, the theory of real competition is both highly realistic and highly abstract. It does not introduce any obvious falsehoods as assumptions. It can also be subjected to all sorts of empirical tests, both of its assumptions and its consequences.

Now whether Shaikh has thought through the implications of real competition correctly or not is important but beside the point here. No one will mistake his theory for a consensus viewpoint, but that also is beside the point. Perhaps it a stretch but my point is simply that Shaikh’s methodology is an example of a theory from the social sciences that resembles some of the interesting points raised by Franklin (and by others in the realist tradition).

Although a realist philosophy of mathematics could never, I don’t think, provide all the required ingredients for a realist philosophy of social science, I still find Franklin’s ideas insightful and provocative. Franklin has already written his own book on science and truth, titled What Science Knows: And How It Knows It. I have not yet read it but I look forward to it.

References

Berth Danermark, Mats Ekström, and Jan Ch. Karlsson (2019). Explaining society: critical realism in the social sciences. Routledge.

Connor Donegan (2025). ‘Probability and the philosophies of science: a realist view’. SocaArXiv. PDF.

James Franklin (2014). An Aristotelian realist philosophy of mathematics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Milton Friedman (1993). Essays in positive economics. University of Chicago Press.

James K. Galbraith and Jing Chen (2025). Entropy economics: the living basis of value and production. Chicago University Press.

Rom Harré (1972) The Philosophies of Science. Oxford University Press.

Harold Jeffreys (1998 [1961]). Theory of Probability . 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

Andrew Sayer (1984). Method in social science: a realist approach. Routledge.

Andrew Sayer (1981). ‘Abstraction: a realist interpretation’. Radical philosophy 28: 6—15. URL

Anwar Shaikh (2016). Capitalism: competition, conflict, crises. Oxford University Press.

Notes

-

Franklin presents part of his own argument in this way, to the effect that we can learn much about logical probability through the example of mathematical problem solving because the subject matter (mathematics) is free from a number of complicating factors, especially from contentious philosophical questions about the nature of causality. ↩

-

Unsurprisingly, Box’s dictum seems to be most popular in statistics. I’m avoiding that topic in this post because the terrain of theoretical debate is so different in statistics. One might expect the realist to adopt the view that probabilities must have an objective or mind-independent existence (in order for the theory of probability to be valid), but that is not the case. The phrase ‘the true model’, in reference to statistical models per se, assumes something dubious. If we know one thing about our observations it is usually that they were not generated by any statistical model whatsoever. The most developed realist view of probability holds that probability is part of logic or epistemology, in which case probability ‘exists’ but only in the way that logic does, not in the sense that my hand exists. ↩

-

The distinctions I am touching on here are described clearly by Rom Harré in his The Philosophies of Science as the successionist (empiricist) and generative (realist) views. ↩

-

Some of the theoretical implications of turbulent arbitrage are complicated and contentious. The elements that I’ve described here are far less contested, if not mundane, and I think the example stands without the need to consider whether Shaikh himself has worked out all the right implications and all the details. ↩

-

When we step back and examine the system from a distance, we see not chaos but rather all sorts of familiar patterns (waves of growth followed by devaluation and recovery, for example). To continue with the point about writing down theories that can possibly exist, Shaikh is careful to say that the regularities generated by the capitalist system are patterns that emerge from the chaos due to specific systemic constraints. The constraints are not ‘steely rails’ but rather ‘moving limits whose gradients define what is easy and what is difficult at any moment in time’ (5). For example, it is difficult for one with little working capital to succeed in competition with a transnational corporation; hence, corporations tend to crush small competitors, and capital tends to congeal into large concentrations which compete fiercely with one another. The concept of ‘systemic constraints’ that he’s applying strikes me as a theory that very credibly describes something about capitalism as a really existing system. ↩