Florida's Convict Leasing Program

Under the State of Florida’s convict leasing program (1877-1919) approximately 14,000 Floridians and visitors served sentences of hard labor at the pain of the lash. Prisoners labored in some of Florida’s first phosphate mines and were leased to turpentine and lumber operations throughout the state. This research, which began as my master’s thesis at UBC, draws on over four decades of reports on the prison system by its administrators in the Florida Department of Agriculture, geographic sentencing data, data on prisoner characteristics, minutes from the Board of Pardons, and additional materials held in the Convict Lease Subject Files in the Florida State Archives.

This study engages with a number of questions revolving around the inter-connected themes of violence, labor, and race. This page provides a summary of the research followed by a (pre-print) copy of the work published in Florida Historical Quarterly. The pre-print contains some supplementary material (images and an original document) not present in the FHQ article, as well as a minor correction to the text (the second paragraph beginning on p. 27 is missing from the original publication). The publication can be found at https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol97/iss4/.

Origins of the lease

The convict leasing program began with the fall of Florida’s (Republican) Reconstruction government in 1877 to the (Democratic) “Redeemers” who aimed to restore white supremacy and, with it, the unbridled power of the owners of capital. On March 2, 1877 the Florida Legislature authorized funding to convert the Florida penitentiary into an insane asylum, and the next day they approved an act granting the governor the power to lease the prison population to private interests.

Under the convict leasing system, private individuals and corporations were to pay the state and, in return, take full possession of the entire prison population. They would exploit the labor of prisoners, at the pain of the lash, in their private industrial or agricultural enterprises. By the end of the convict leasing system in 1919, approximately 14,000 Floridians and visitors had served sentences in a sprawling network of private labor camps located throughout the state. After 1900, most prisoners were leased to the rapidly expanding lumber and turpentine industries which, as of 1910, comprised over 37,000 wage earners and made up 65% of manufacturing employment in Florida.

A labor market institution

As the FHQ article documents, nothing like due process existed in the Florida courts. Many prisoners were pardoned, but pardons were often granted only after the claimant had become debilitated from hard labor, violence, or disease. Coercive forms of state power—arbitrary sentencing power exercised by the courts, “false-pretense” laws that supported debt peonage, the notorious cruelty of the penal system—contributed to the proliferation of tyrannical labor relations, not least of all in the lumber and turpentine industries.1

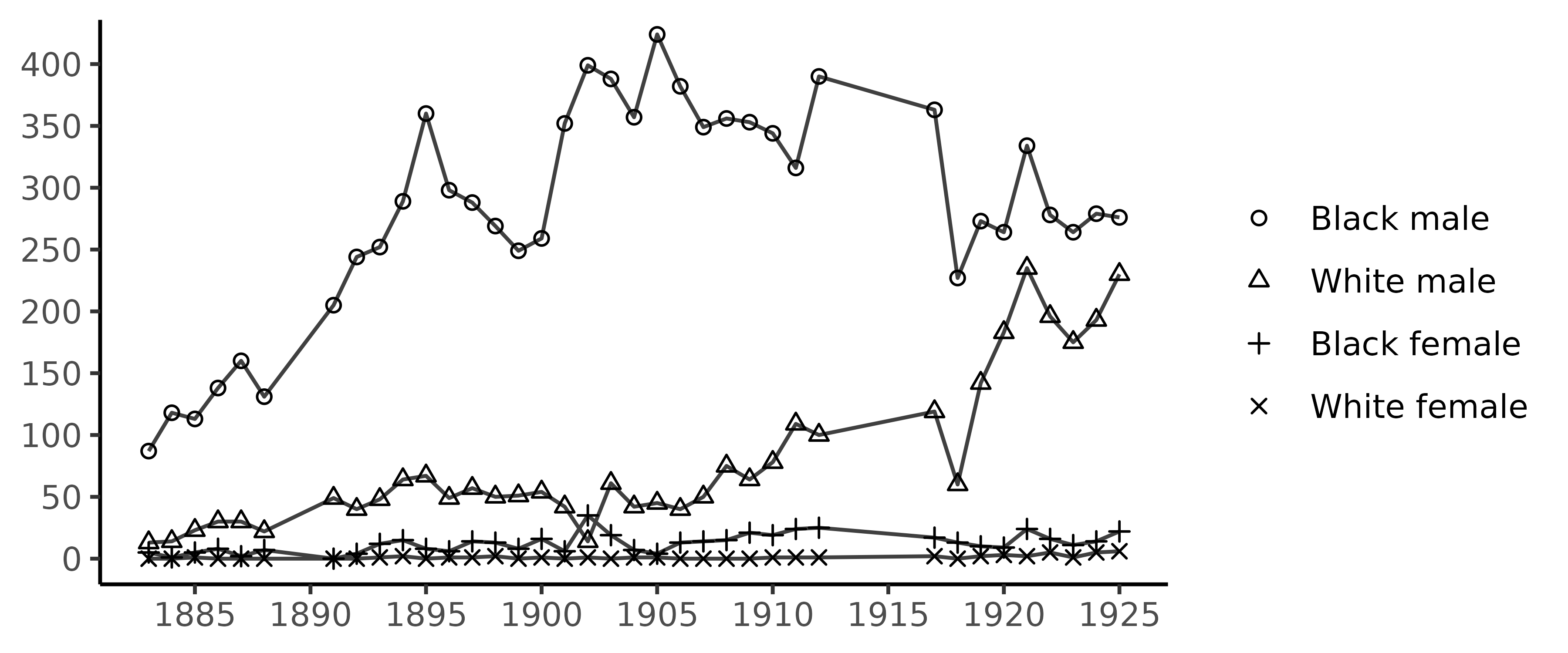

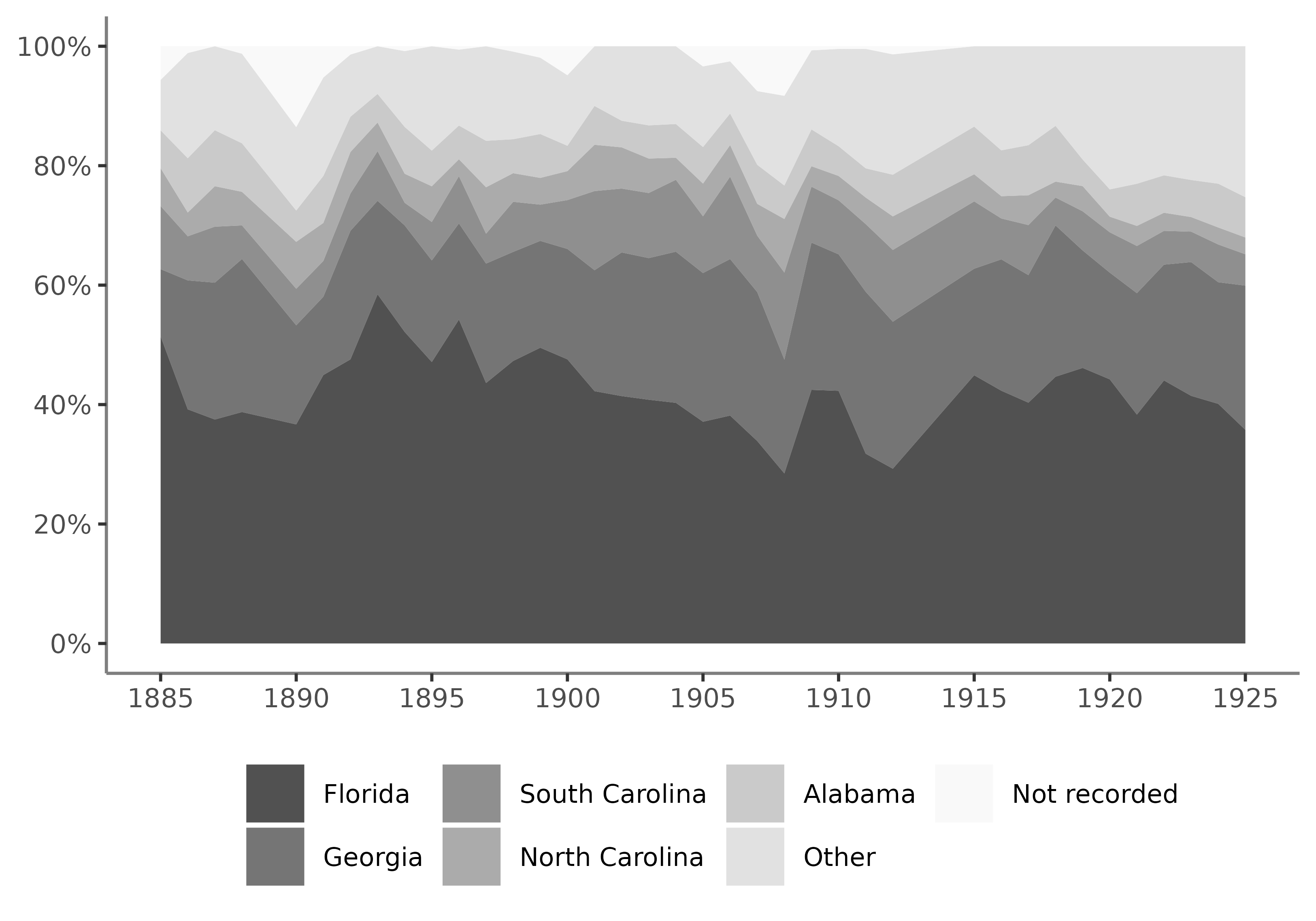

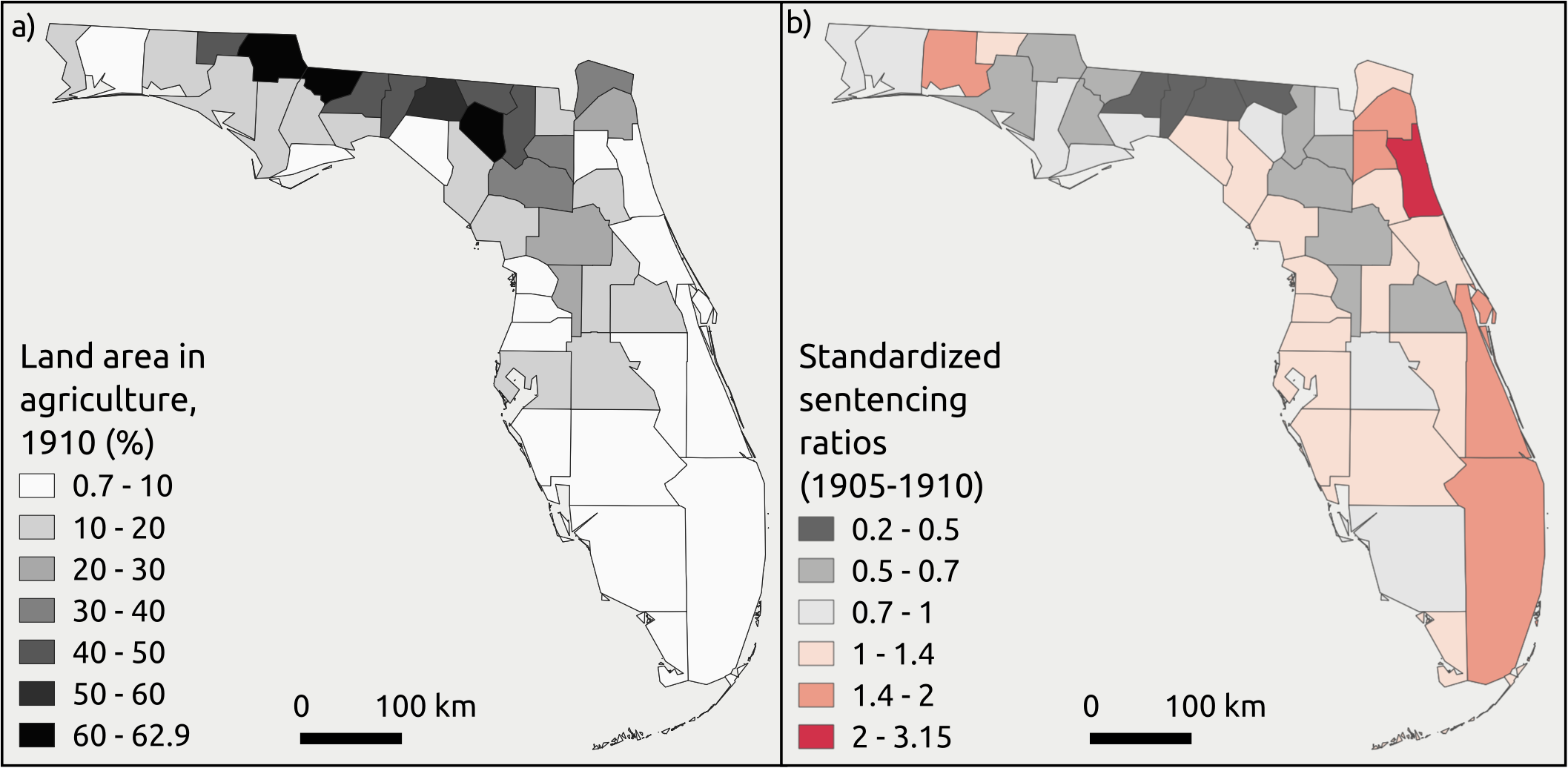

In an important account of convict leasing in Georgia, Alex Lichtenstein suggests that the threat of prison labor would serve as “a powerful sanction against rural blacks who challenged the racial order upon which agricultural labor control relied.”2 This forms part of Lichtenstein’s argument against the common presumption that there was a conflict of interests between industrial capital and the labor-repressive plantation regime. In Florida, it seems that many prisoners already belonged to the massive black migrant workforce that powered lumber and turpentine operations in Florida; over half of Florida’s prisoners hailed from outside of the state (Fig. 2). Not only were most prisoners from out of state, most were also sentenced in counties that are outside of the state’s plantation belt, where agricultural production was concentrated (Fig. 3). The prisoners belonged, according one prison official, to a “criminal class” that “should labor, should be wealth producers in or out of prison.” These “wealth producers” were not to be the one’s who enjoyed such wealth. Rather, prisoners were expected “to learn the lesson of obedience, submission and energetic effort or labor.” On that reasoning, the system served as a disciplinary institution with respect to (black) labor. The evidence indicates that this disciplinary force was at least as important outside the plantation economy as within it.

After clear-cutting its way through various other states, the lumber industry expanded into Florida’s pine forests while deploying a range of exploitative and violent labor arrangements, from simple wage-labor to debt peonage to the quasi-slavery of the prison laborer, all under intensely competitive market conditions.3 Labor scarcity in remote forested areas was often an issue for operators, but workers themselves were unable to leverage this to their advantage to push for better conditions and pay. Instead, operators kept “woodsriders,” armed overseers on horseback, to prevent workers from leaving their employment. The exercise of coercive forms of state power buttressed the unbridled authority of employers and stands among the primary reasons why forced labor proliferated in the forest industries in Florida and other southern states.

Race as ideology of social fitness

The supposed “healthfulness” of the prison population was a recurring, and highly contentious, theme of both administrative reports and political debate. In official reports and professional conferences, Florida prison officials aped the latest pseudo-scientific theories of race and social fitness. This was an effort to naturalize the prevalence of death and disability among prisoners in their custody. Prison officials repeatedly claimed—against the available data—that the death rate among prisoners was less than that among “free citizens.” Not only were death rates higher than among the Florida population, but the age distribution of the prison population renders the comparison absurd: most prisoners who died were in the early years of adulthood.

The stem-and-leaf plot below presents the age of each prisoner who died between the years of 1905 and 1909. The deaths are broken into five-year age groups; the first line includes all deaths for ages 10–14, the second line includes all deaths for ages 15–19, and so on. The digits to the left of the vertical lines represent the first digit in the ages of the prisoners who died; each digit to the right represents the second digit in the age of a prisoner who died. So 1 | 4 indicates that one fourteen year-old prisoner died; so too did four of age eighteen (1 | 8888) and five of age nineteen (1 | 99999). Most prisoners who died were in their twenties or early thirties; 75% of in-custody deaths were of persons under age 35.

Ages of prisoners at time of in-custody death, 1905-1909 (N=124) 1 | 4 1 | 888899999 2 | 00011111112222223333444444444 2 | 555566666666777777777888888899 3 | 000000001111112222233444 3 | 555666788999 4 | 000022233 4 | 5677 5 | 013 5 | 6 6 | 0 6 | 5 6 | 5 = 65 years old

Saving the system

Among the formerly Confederate states, all but Virginia were leasing state prisoners by 1880. By 1900 the political tide seemed already to have turned against convict leasing and towards public road work and state-run farms. Mississippi, South Carolina, and Louisiana had all abolished the lease. Georgia soon followed suit, ending convict leasing in 1908. Riding a growing wave of public sentiment against monopoly power and corruption was Florida Democratic gubernatorial candidate William Sherman Jennings. Jennings promised to fill the public coffers by breaking the cartel of lessees (who he claimed were colluding in the bidding process) and to improve the treatment of prisoners at the same time. Jennings won the election, and served as Governor from January 1901 to January 1905.

As opposition to convict leasing mounted, Governor Jennings and prison officials worked to forge a new public image for the penal system and its wards. The system could be both just and profitable, they argued, if only punishment was measured and properly administered. Prison officials in the Jennings administration drew up new regulations and standards for whipping bosses and facilities.

The reforms proved to be hollow. Prison supervisors sometimes documented but did not prevent barbarous treatment. Prison physicians actively colluded in managing the exploitation of so-called “hospital subjects,” leasing disabled prisoners at discounted rates that were set to match the supposed labor abilities of each “hospital subject.”

Nonetheless, the reforms breathed new political life into the system.

Demise of the lease

By all appearances, those who leased prisoners tended to treat white male prisoners similarly as they treated black male prisoners. White prisoners could also be brutalized and worked to the brink of death. Though most prisoners were black males, white male prisoners were always present, and they introduced a political problem for defenders of the lease.4 The prison system became segregated only within the last two to three years of the convict leasing program.

A key political turning point came with the following public admission by prison physician Dr. Robert Kennedy:5

hospital subjects consist mostly of men who have been beat up or worked to death…on turpentine…Some are physical wrecks and can never again hope to enjoy sound health.

Kennedy’s statement contradicted decades of official reports and sparked a new round of investigations and disturbing revelations. The State of Florida’s convict leasing program was abolished by Chapter 7833 of the Legislature, effective December 31st, 1919.

The new law said nothing of county prisoners who continued to be leased to private interests. A national uproar over the murder of Martin Tabert, a young white male from North Dakota, finally moved Florida officials to action. In a familiar sequence of events, Tabert was worked to exhaustion and then beaten mercilessly in front of dozens of fellow prisoners. He was left on a cot to die and ignored by the camp physician who later participated in the cover-up. On May 24, 1923, following an investigation by the Florida Legislature, Governor Cary A. Hardee signed the “Convict Anti-Whipping Bill,” ending corporal punishment and, the following day, abolished county convict leasing.

Pre-print

Donegan, Connor (2019). The making of Florida's "criminal class:" race, modernity and convict leasing program, 1877-1919. Florida Historical Quarterly 97.4: pp. 408-434. Open access pdf (with images): doi:10.31219/osf.io/2wj7s

Notes

-

For much more on labor relations in the lumber and turpentine industries, see Aarron Reynolds. “Inside the Jackson Tract: The Battle Over Peonage Labor Camps in Southern Alabama, 1906”. In: Southern Spaces (January 2013). https://southernspaces.org/2013/inside-jackson-tract-battle-over-peonage-labor-camps-southern-alabama-1906. Other studies that link convict leasing and the generally repressive legal system to labor-repressive regimes include: Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South. Verso, 1996; Bobby M. Wilson, America’s Johannesburg: Industrialization and Racial Transformation in Birmingham. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: 114–121. These issues as well as gender are covered by: Sarah Haley. No mercy here: Gender, punishment, and the making of Jim Crow modernity. UNC Press Books, 2016; Talitha L. LeFlouria. Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South. UNC Press Books, 2015. ↩

-

Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (London and New York: Verso, 1996), 13. ↩

-

The language used here to discuss forms of exploitation, and the implicit argument that such formal and legalistic variations do not imply a departure from capitalist commodity production, is borrowed from Jairus Banaji, Theory As History: Essays on Modes of Production and Exploitation. Brill, 2010. ↩

-

For more on the factors contributing to the end of convict leasing, see Matthew J. Mancini, One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866–1928. University of South Carolina Press, 1996. ↩

-

This quotation and the political events surrounding it, as well as Martin Tabert’s death, are mainly gathered from: Noel Gordon Carper. “The covict-lease system in Florida, 1866-1923.” PhD thesis. Florida State University, 1966: 141–153, 297–299. ↩